Alright, so we’ve covered the character pinyin and pronunciations. Now there’s one final piece to introduce: tones. Tones are often discussed as one of the more difficult aspects of the Chinese language. I hope this post will help demystify the tones for you so you understand them much better. With a full understanding, you can jump straight into learning the tones for specific characters.

** I want to make a quick disclaimer to make sure there is no confusion. Chinese tones are very important. Using the incorrect tones or no tones at all in your speech can make it very difficult for you to be understood, even in context, let alone when trying to use characters or words out of context. If we are saying a word and using the incorrect tone, let’s be clear that we are undisputedly saying the word wrong altogether. The tone is as much a part of the character as it’s pinyin, so you should never expect that you can completely ignore tones. **

Mandarin Chinese utilizes 4 tones (plus one neutral tone) to attach meaning to characters. However, a common misconception of tones is that it has something to do with singing or musical tones. That is, people often think they would have to be able to recognize specific musical tones to learn this concept. This is absolutely not true. Tones are actually a lot more like the stress that we put on words in the English language. You’ve probably never noticed it, but English also uses similar “tones” to convey meaning. Take the following example, how does the meaning of the following sentence change by placing the stress on different words?

- I didn’t say that. – Neutral

- I didn’t say that. – Suggesting someone else said it

- I didn’t say that. – Defensive

- I didn’t say that. – Suggesting I conveyed it somehow, but not by saying it

- I didn’t say that. – Suggesting I did say something, just not that.

These sentences all contain the same exact words, but the stress completely changed the implied meaning. This is a concept that can be very difficult to grasp for non-native English speakers. Let’s imagine a situation in which you said sentence number 2, but you meant sentence number 5. It would be quite confusing to the listener, who might need another sentence or more of context before they realized your mistake and they would probably still need you to clarify. This is similar to what can happen when you speak in Chinese while using the wrong tones, only the resulting difference in meaning can be much greater.

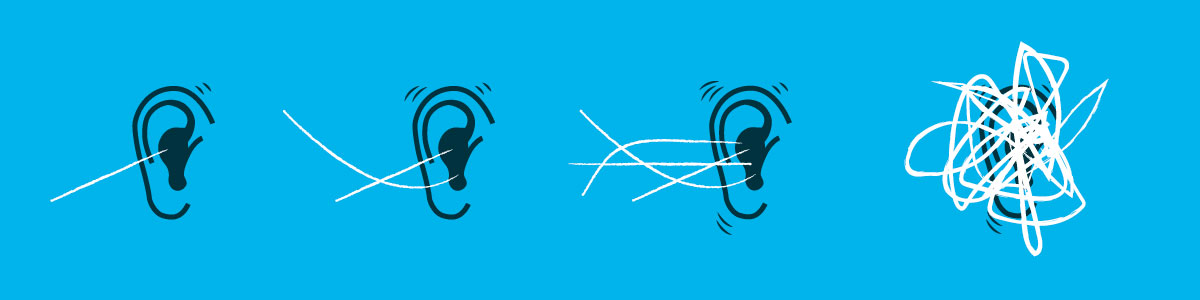

Similarly, it’s not uncommon as an English speaker to change the inflection of your voice to give additional meaning to the sentence. For example, let’s look at the sentence, “You live in New York.” But instead of saying it with a neutral stress, you raise the pitch of your voice on the last word. The sentence now becomes a question: “You live in New York?” In fact, we will discuss later that the 2nd tone in Chinese is actually very similar to the inflection of that last word.

Now, Chinese has many many homonyms; this is one of the reasons people often find it so difficult. For example, even of the highest frequency 600 words, about 3% have the exact same pinyin of “shi” in one of the 4 tones. I was able to understand tones a bit better after thinking also about the number of homonyms in the English language. There are some examples of English homophones where context is necessary to clarify the meaning. For example: read/red, where/wear, two/to/too, one/won, etc.

I like to think of Chinese similar as to this, just with a whole lot more homophones. The difference is, in Chinese a lot of these homophones have the same pinyin, but the tones are used to clarify meaning instead of context. Take the following words as an example:

北京 (běijīng) – Beijing

背景 (bèijǐng) – background

上海 (shànghǎi) – Shanghai

伤害 (shānghài) – to harm

使用 (shǐyòng) – to use

实用 (shíyòng) – practical

适用 (shìyòng) – applicable

买 (mǎi) – to buy

卖 (mài) – to sell

In the following examples, I like to think of tones as actually making your life easier, not harder, because the tone is the only thing that makes the different homophone meanings stand out.

Just to clarify though, the examples I’ve shown here were chosen specifically to highlight this phenomenon. Most words contain two characters and many two character combinations (and their pinyin combination) are actually unique. So I think that people often really over-exaggerate when they say things like, “I hear Chinese is difficult because if you say the word wrong, it has a completely different meaning.” While that’s true for some words, the majority of words you will use in context would not be immediately mistaken for a specific alternative word with a different meaning if you used the wrong tone. Instead, it would just sound completely wrong and potentially be confusing to the person trying to work out what you are saying. It would be like trying to understand someone speaking English who’s putting emphasis on all the wrong syllables.

My recommendation (and also a recommendation I was given) for learning tones would be to try to learn the tones from beginning, but only to the extent that it is not slowing you down in learning the most frequently used 600-1000 characters. If certain tones just won’t stick in your mind, I suggest moving on to learning more characters so that you never slow down your progress building up the base of characters. Once you know this set of characters, starting to read content of any difficulty level will be surprisingly approachable. I found this is the time when it became crucially important for me to go back and ensure that every single time I read a character, I forced myself to say the tone aloud or in my head until they were cemented in my memory. I find that tones both feel more natural and are way easier to remember when you can associate them with several words containing a common character rather than studying tone for the character by itself.

Ultimately, the goal of this guide is to equip you with everything you need to start reading and watching content that you are actually interested in as soon as possible. If you can find content that you are reading because you are interested in it, and not just because it’s in Chinese, you will find that your growth is much faster and more enjoyable. Once you have the ability to start reading and really enjoying using the language, this is when you should make sure you are steadfast in focusing on the long term familiarization with tones. Now we’ve discussed how tones work and their relationship with characters. But we still need to go into detail about each of the 4 tones and talk about how to recognize them. We’ll cover this in the next post.

Next up: The 4 Tones

How to get started learning Chinese Series

Background Understanding of the Chinese Language

The Part You’re Excited and Worried About: Chinese Characters

Things Just Got a Whole Lot Easier: Pareto’s Principle

Learn About Pinyin

Get an Overview of Pinyin Pronunciation

Chinese Accents

Tones Aren’t So Scary

The 4 Tones

Tech Pit Stop: Setup Chinese Input on Your Computer

Tech Pit Stop: Setup Chinese Input on Your Phone

Tech Pit Stop: Must have Apps for Your Phone

Get an Overview of Chinese Grammar

Pick a Go-To Source of Chinese Reading Material

Beginner Series Summary