It will be really helpful from day one if you’re able to input Chinese on your phone. This can be quite useful for dictionary lookups, Google Translate, texting on WeChat, and many other things. (We’ll discuss some of these apps later on).

-On iPhone: Go to Settings > General > Keyboard > Keyboards > Add New Keyboard… > Chinese (Simplified) or Chinese (Traditional).

Now that your keyboard is setup, you can easily access it an any application by pressing the globe key on your keyboard to cycle through your installed keyboards. Just like the computer input method we discussed in the last post, iPhone will offer different options of characters as shown in the animation below.

-On Android: Unfortunately, I don’t have an Android phone to play around with and create as much detail as I did above for Apple products. But

Next up: Tech Pit Stop: Must have Apps for Your Phone

How to get started learning Chinese Series

Background Understanding of the Chinese Language

The Part You’re Excited and Worried About: Chinese Characters

Things Just Got a Whole Lot Easier: Pareto’s Principle

Learn About Pinyin

Get an Overview of Pinyin Pronunciation

Chinese Accents

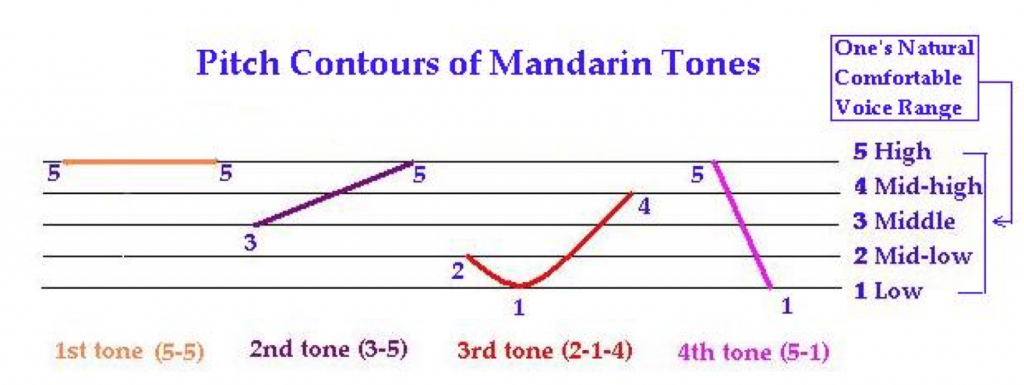

Tones Aren’t So Scary

The 4 Tones

Tech Pit Stop: Setup Chinese Input on Your Computer

Tech Pit Stop: Setup Chinese Input on Your Phone

Tech Pit Stop: Must have Apps for Your Phone

Get an Overview of Chinese Grammar

Pick a Go-To Source of Chinese Reading Material

Beginner Series Summary